Travellers to strange and distant realms, and anyone who has ever seen the film Lost in Translation (Sofia Coppola, 2003), knows the mixture of desperation, disorientation and melancholy that catches up with a tourist who stays any length of time in foreign lands. Jewellery maker Ruudt Peters had a similar experience during his stay in China in 2012. Apart from the overwhelming presence of billions of Chinese, it entailed being immersed in a country that appears to be losing itself in lightning-fast economic and social developments. At the cultural level the Chinese penchant for collectivism, which reaches back to the Confucian predilection for harmony, is the most obvious difference. It is no wonder that Ruudt Peters, who as a Westerner and an artist in fact has a double dose of individuality, often felt himself to be a castaway in an ocean of Chinese. At the same time his sensibility as an artist enabled him to transform the experiences which he encountered during his stay in China into a productive substratum for his creative process. Peters brought about this transformation in two ways: first by constructing a thematic bridge to the rest of his oeuvre, and second by making use of China's status as the workshop of the world.

With regard to the first point, the thematic link between this recent work and the rest of his oeuvre, the bridge was obvious: alchemy. Alchemy is, it so happens, undeniably a (if not the) leitmotif in Ruudt Peters's oeuvre. For a jewellery maker – a discipline in which metals (precious and otherwise) and gemstones traditionally play an important role - that is not an unusual source of inspiration. Thus it is equally no surprise that Peters, while visiting China, should delve into the Chinese alchemistic tradition, although the outcomes of his investigations are.

During his stay in China, which included a period working at the C.E.A.C. (Chinese European Art Center) in Xiamen, the differences between the Western and Chinese alchemistic traditions quickly became clear to him. Chinese alchemy is more oriented to the inner self and to the life force, Qi. This word has therefore become the all-encompassing title for the series of works which have arisen out of his visit to China.

In the Western alchemistic tradition, in which Peters is well grounded, the emphasis has historically been more on the materialistic aspects, chief among which has been the transmutation of lead into gold.

Peters's explorations of Chinese alchemy led chiefly to the insight that it formed a world, if not a cosmos, of its own. While it was impossible, during the time he was there, to thoroughly investigate this, on the basis of the knowledge he already had and the fact that the various alchemistic traditions do necessarily overlap, he was able to develop a general picture of the situation. Moreover, alchemy is not an exact science. It is rather a 'proto-science', in which the intuitive prevails over the rational.

That intuitive element also contributes to the fact that the theme of alchemy is so fascinating to Peters. It engages well with the way in which he creates his work. For instance, for years now he has used blind drawing as a way to disconnect from the rational and come directly into contact with the subconscious. While staying in China he registered the daily deluge of impressions in this manner.

The second method by which Peters succeeded in building a bridge between East and West is an extension of this way of working. He had Chinese handcraftsmen execute his work under his supervision. In itself, this is far from unusual. It is just that where most clients frenetically attempt to retain control, Peters sought the point at which he risked losing control.

He went the farthest in this in the three series of works in which his drawing method has been given its most direct repercussions, the brooches, pendants and steles. Blind drawings from his travel diary appear on the brooches and the pendants, entitled Hun, which means 'soul'. These drawings were transferred onto freestone in a workshop by craftsmen. Blind drawings were made on photos of the brooches, which after their arrival in Amsterdam were translated into lines in silver on the freestone brooches. In the case of the steles – Ba xian (immortal 'saints' from Taoist tradition) – the original drawings were transferred 1 : 1. The artist could only direct any of the steps at which he was not present in person by means of e-mails and photos. This manner of deliberately letting go of his control over the artistic process (at least partially) allows the works to liberate themselves from individual experience, attaining universal expressiveness.

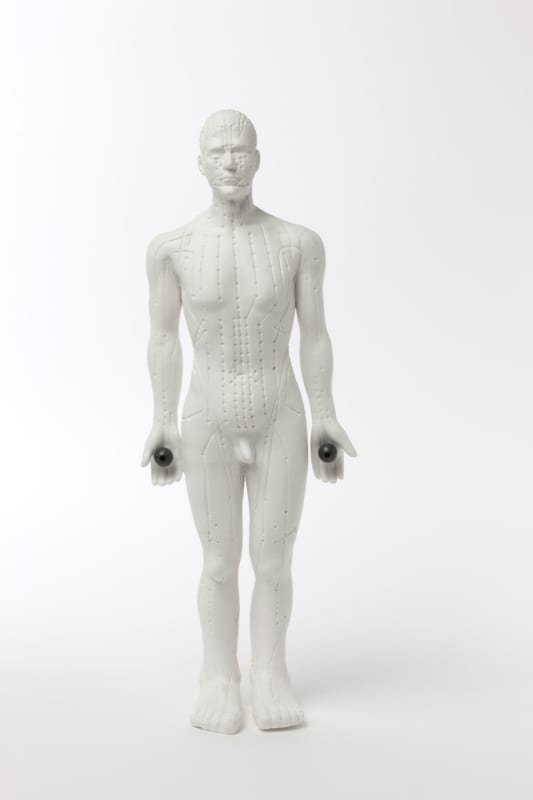

A good example of how Ruudt Peters translates a personal experience into an artwork is found in the group of 99 human figures entitled Cun zai (being/ to be). This work arose from a visit to the terracotta army of Emperor Jing Di. In contrast to the terracotta army of Xi-an, this lesser-known army was realized at half life-size. In addition, Jing Di's soldiers are no longer standing in ranks. After their clothing and moveable wooden arms rotted away, they tumbled over on one another.

This confusion of half-humans resonated so powerfully with Peters that he wanted to assemble his own army. Ultimately that became a company of 99 men. Following the 'dissociative' approach described above, he had moulds of meridian models from acupuncture combined and transformed by others. Subsequently he himself, in China and back in The Netherlands, made additions referring to specific experiences during his trip to China, transforming the uniform mass into a collection of individuals.

This sculptural group therefore best embodies the synthesis between East and West that Ruudt Peters has achieved with his manner of working. In drawing on his knowledge of Western alchemy to delve into Chinese alchemy, he has, in a quite spontaneous manner, been able to make substantive connections between his oeuvre as it has developed to this time, and becoming acquainted with another culture. As a result, these works are not Fremdkorper within his oeuvre.

More important, however, is the detached manner in which the work has been created. Peters, as an artist, and as an individual, has consciously kept his distance. In this way he has allowed something of the Taoist thought and the collectivism which is so definitive for Chinese culture to enter into his artistic process. And in this way Peters also refutes Rudyard Kipling's famous lines, “East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.”

By letting go of the Western notion of authenticity in favour of a more collective and disengaged approach to the work, he has generated unexpected and ambiguous results. For example, both the weather-beaten faces of the ba xian and the Chinese mountain landscapes that are often depicted on paper scrolls can be discerned in the drawings on the steles.

Ruudt Peters did not journey to the Far East in quest of truth, as have so many others before (and after) him. Yet it would seem that he wants to share a piece of wisdom with us in these works.

Perhaps it can be phrased as follows: lost and found are two sides of the same coin.

Or did I read that in a fortune cookie somewhere?

Fredric Baas MFA

curator Stedelijk Museum s’Hertogenbosch NL